The new viral battlefield

Since 2016, a battle has been waged for the soul of social media, with tech companies embroiled in controversy over their ability to conduct content moderation at scale. How many hundreds of thousands of moderators are necessary to review potentially harmful information circulated to millions of people globally on a daily basis? When tech companies resort to conversations about scale, they are really talking about profits. For social media companies, each new user is also a source of data and advertising revenue. Therefore, the incentive to scale to unmoderatable size outweighs public concerns over the harms caused by “fake news” outlets or coordinated “pseudoanonymous influence operations,” in which foreign and domestic agents employ deceptive tactics to drive political wedge issues. While these abuses of social media now color discussions about the role the tech sector should play in society and to what degree these companies’ products affect political outcomes, much less attention has been paid to other forms of content, such as memes, and how they are used in political communications.

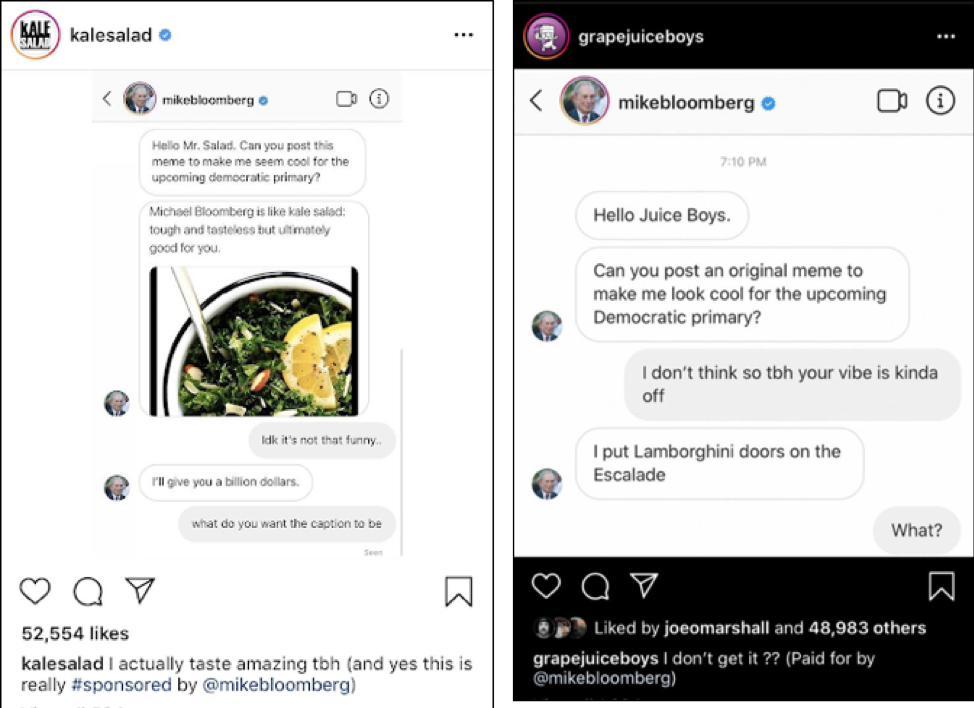

For example, rather than try to spin up his own social media empire in February 2020, Democratic presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg paid already-popular Instagram influencers to meme him into the race. Instagram was slow to respond to this misuse of their platform, where account holders are supposed to label sponsored content and log it with the company. Because this approach was more akin to an advertising campaign, it didn’t go viral in any contemporary sense of the word.

Mainstream media picked up the story because it was a novel use of social media, and many commentators across mainstream and social media relentlessly mocked Bloomberg for cringeworthy content. Even the social media accounts promoting Bloomberg’s candidacy seemed lukewarm on his presidential bid. This commercialization of memes led some to criticize these influencer accounts for merely aggregating and monetizing the work of memetic communities. As the 2020 US election looms, platform companies are now taking the lead on stricter content moderation, which means those who own the means of communication own the memes of cultural production.

While memes may never tip an election one way or another, they are increasingly used in persuasive political communications by politicians, pundits, foreign agents, marketers, ideologues, and ordinary folks, compelling journalists to cover memes as part of the political beat. In this essay, I ask, when does a meme become disinformation?

What is a meme?

Memes are a crucial part of our contemporary communication environment, where play and politics often collide. Whereas Generation X spent hours crafting elaborate covers for mixtape compilations, the youth of today use meme-making as a fun and creative outlet. Memes are defined as “an idea, behavior, style, or usage that spreads from person to person within a culture,” but contemporary research about memes centers on internet culture specifically, usually the use of images to spread ideas quickly. When memes draw out the irony and contradiction of current events, they can also be a form of persuasive political content. Since the US 2016 election, memes have grown in popularity as a style of political participation across all social media platforms, joining together both positive and negative ways of interacting with political campaigns.

Great memes do not promote a specific campaign, candidate, or policy position. Instead, popular memes tend to have four main qualities: (1) anonymous authorship, (2) the creation of insiders/outsiders, (3) stickiness, (4) and participatory dynamics. Memes tend to be shared when they lack attribution, when they connect with small groups who get the inside joke, and when they have a memorable turn of phrase, slogan, or pithy caption. If done well, audiences will both share and then remix the template with their own additions as playful political participation.

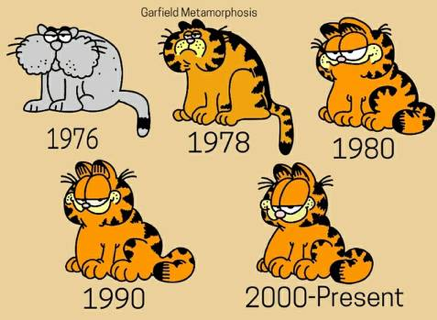

Richard Dawkins describes memes as “units of culture” that are passed between groups and from generation to generation. Memes don’t have to be images, but are rather ideas that are mediated in some form or another. For example, “Grumpy Cat” is arguably one of the most famous online memes, but earlier iterations of disgruntled and mischievous cats predate this contemporary ideation, like the Cheshire Cat from Alice in Wonderland (1865), Tom from Tom & Jerry (1940), and Garfield (1976). Like an archaeologist, memeographers can take these images and keywords, and map how they show up within a networked data infrastructure over time.

More than just playful humor, memes now serve an important role in political communication. At Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, I lead the Technology and Social Change Research Project, a team tracking the use of memes by political campaigns. While it is difficult to study the propagation of media manipulation and disinformation campaigns across platforms for a variety of reasons, image-based memes can be tracked using reverse image search and ethnographic methods, such as process tracing and timeline analysis. Our approach looks at how different memes are generated and how they trade up the chain, from anonymous message boards through social media and eventually into a politician’s campaign materials. Of course, communication is messy, and messages that don’t resonate in one context might spread like digital wildfire in another. Sometimes memes might sit for years before becoming popular. Other times, politicians may try to “force” a meme into popular culture, which can set off a riotous onslaught of humorous and sarcastic reactions.

Memes are now a particularly murky issue for tech companies because they often employ satire, which is difficult to moderate as context is often unclear. Data scientists, communication scholars, sociologists, and other researchers have studied the strategic use of memes in political campaigns, but much more research needs to be done on the usefulness of memes in media manipulation and disinformation campaigns. In the landmark study The Oxygen of Amplification, Whitney Phillips historicizes how online trolls and other decentralized networks understood the enormous political potential encapsulated in memes that go viral across social media. Users of the anonymous message board 4chan developed a style of coordinated participation across the web and social media platforms that could catch the attention of journalists, set media agendas, and frame coverage of political candidates and breaking news events.

While no single meme will likely compel any significant change in voting outcomes, memes certainly color the contemporary experience of digital democracy. In fact, an influence operation in 2016 carried out by Russia’s Internet Research Agency (Ru-IRA) attempted to sway US voters using a variety of persuasive techniques, including memes. While academics debate if the Ru-IRA had any significant impact on voting behavior, netizens continue to participate in fourth generation warfare, “where lines between combatants and civilians are blurred in warfare conducted across a comprehensive front combining political, economic, social and physical combat,” as described by Travis Wall and Teodor Mitew.

The networked terrain of the web and social media creates numerous possibilities for political action, as people’s public and private lives intersect across borders, professions, and institutions. Here, I will describe some of the mechanisms mobilizing participation in meme wars and what the terrain looks like for the US 2020 elections.

Why do people make political memes?

Meme-making is rarely a profitable practice, but those who run social media accounts that curate memes can make money off of sponsored content and ad placement. Instagram, in particular, has become a crucial platform for memetic entrepreneurs, who harvest memes from different places online, like message boards and social media, and repost them. With this strategy, some accounts have managed to gather massive followings, allowing them to sell spots to advertisers, marketers, politicians like Bloomberg, and other interested parties.

Monetizing the US partisan divide is yet another way that zoomers—digitally savvy gen z conservatives—are capitalizing off of the open economy on social media. Jesselyn Cook of the Huffington Post interviewed conservative Trump-supporting teens who utilize Instagram and TikTok to spread bombastic content. While these account administrators rarely create their own memes, they are making money off virality: the more outrageous the meme, the higher the engagement. Brands go looking for up-and-coming accounts in which to place sponsored content, including selling MAGA-themed clothing.

While money can be one rationale for participating in online trends, most sharing is done for very banal reasons, including most significantly because their friends are also doing it. In this way, making a meme go viral isn’t easily purchased. Because viral distribution tends to rely on ingroup dynamics, it is nearly impossible to replicate this within political campaigns, unless the meme can engender a sense of familiarity or parasocial relations between constituents. Everything else is just advertising.

Political meme factories

Except in the case of Bernie Sanders, most attempts to use memes during the Democratic primaries were met with a shoulder shrug from online audiences. On Super Tuesday (March 3, 2020), a surge of memes blanketed social media platforms in support of Sanders’s campaign, with others busily dunking on his opponents Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren, Michael Bloomberg, and Pete Buttigieg. While memes are often created by anonymous individuals and iterated on by groups, political memes tend to get attributed to the handiwork of a candidate’s campaign staff.

For example, the sometimes-obnoxious Sanders supporters—nicknamed “Bernie Bros”—went to great lengths to ensure the domination of his campaign across social media. Sanders supporters made significant use of “organic” content by shuttling memes from platform to platform. Organic content consists of posts that are gaining significant engagement without the aid of advertising, search engine optimization, or deceptive tactics. Utilizing a combination of Twitter direct message groups, Facebook pages and groups, and Reddit, Sanders supporters loosely coordinated memetic responses to breaking news events, especially ones that besmirched the reputations of other candidates.

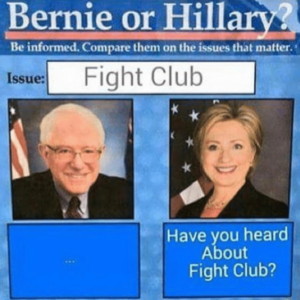

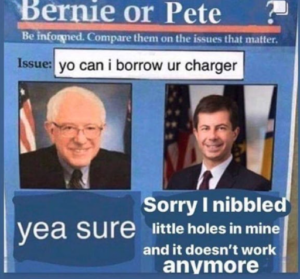

The “Bernie or…” meme template (pictured below) was easy to remix and was often funny. This set of memes positions Sanders as an ordinary and down-to-earth candidate in contrast to his uptight competition. The meme took off in 2016 and was recycled in 2020.

Strikingly, memes criticizing other Democratic candidates were popular with both Sanders supporters and Trump supporters. These factions both criticized Joe Biden by giving him nicknames such as “Creepy Joe” and “Sleepy Joe.” The actions of Democratic supporters bore an uncomfortable resemblance to the right-wingers boosting Trump, and these online attacks fractured the already tenuous ties between Sanders and other Democratic candidates. In the Democratic primary debate, Sanders was directly called out to admonish his online fandom, which he deflected by claiming the vitriolic behavior could have been Russian in origin.

The great meme war of 2016

Meme wars, however, don’t begin and end in Saint Petersburg. They are a feature of social media, which rewards outrageous content with clicks, likes, and shares. For those making and sharing political memes, there is no greater reward than recognition by your favorite politician. As a result, meme-makers try to get a politician’s attention in hashtags and replies, as well as by trying to gain attention of anyone in that politician’s orbit.

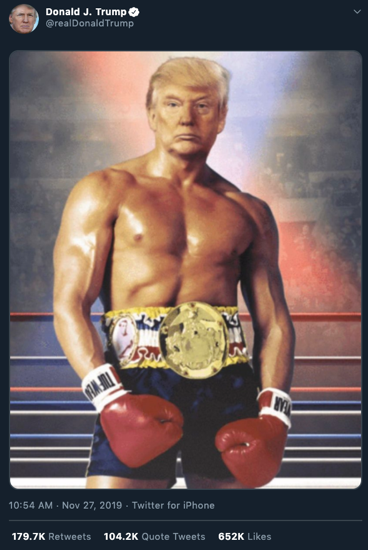

Since 2015, Trump supporters have steadily gained acumen in the creation and distribution of memes, while Trump himself has become the undisputed champion of politicians using memes on social media. Trump will use memes created by his fans in order to drive political issues or to insult his political rivals. For example, recently Trump shared a manipulated video of Biden playing N.W.A’s iconic song “Fuck tha Police” at a recent rally. While Biden did play a song on his phone at the rally, it was simply a popular song by one of the event’s guests. When asked why the president shared the edited video, Tim Murtaugh, Trump campaign communications director, replied, “You call it a fake video. What it is is an internet meme. Those are very frequently done to make a political point.” One thing is clear: Trump’s campaign team knows the value of content made by supporters and has adapted to use the ambiguity of memes like this one to drive the media’s agenda.

The “great meme war” of 2016 stands as the first moment in US election history when numerous political candidates and their supporters battled for control over the networked terrain of social media. Meme wars involve decentralized and anonymous networks propagating political memes for the purpose of political persuasion or community building. Those who were inside the 2016 meme war saw attack after attack waged on Democratic candidates, with Sanders supporters the only group equipped to spar with such a motivated group like MAGA supporters. After the 2016 Democratic National Convention, the MAGA coalition took aim at the Hillary Clinton campaign and were able to elicit key responses. For example, by tirelessly harassing her supporters online, right-wingers provoked Clinton to call them out in a speech where she mentioned the so-called alt-right and posted an explainer on “Pepe the Frog.” Thus summoning the burgeoning MAGA coalition, Clinton became the center of attention among groups of trolls who had been practicing memetic warfare for years.

Trump supporters bunkered down on Reddit and Discord, where they built small armies of trolls who spent countless hours generating content and devising distribution strategies to maximize uptake. Message boards and chat apps became content factories for campaign staffers who needed to recycle content quickly, while some of the meme factories on Reddit were fodder for Russia’s IRA influence operation.

Part of the reason why meme campaigns from MAGA supporters are so successful is their capacity to elicit support by creating feelings of both comradery and outrage, with those opposed to the offensive content sharing it out of anger, entertainment, and disbelief. The algorithms on social media are content agnostic and reward any engagement, so this type of toxic virality relies heavily on negative reactions.

Since Trump’s 2016 campaign, his supporters have remained unrivaled in their capacity to launch a memetic assault on every detractor that passes through their line of sight. From foreign leaders to journalists, and activist groups (particularly antifa and Black Lives Matter) to corporations, Trump’s online base relentlessly bombards critics with memes, onslaughts that veer into harassment. The_Donald subreddit was deleted in 2020 due to coordinated harassment and hate speech, after a long time of quarantine.

Meme wars 2020

The pandemic has taken center stage in the US. As such, public health messaging memes like “flatten the curve” have been replaced by popular memes criticizing Trump’s response while painting Dr. Anthony Fauci as a hero. Groups like the Lincoln Project—Republicans that refuse to vote for Trump—have aligned with philanthropist Reid Hoffman[1] to launch a meme campaign against Trump. The first anti-Trump collaboration from this alliance is a cringe video of Trump “rap battling” Ronald Reagan. This is not a meme, though, so much as an extended political advertisement. While the right has clamored that “the left can’t meme,” the statement points to a broader issue, which is that meme wars are tilted in favor of those willing to use negative stereotypes and cruelty to tap into broader audiences. Memes that invoke racist, sexist, LGBTQ, and religious intolerance resonate with a broad swath of internet users, particularly white men.

For example, the Biden/Harris ticket is understandably drawing the current ire of the MAGA coalition, but the themes are growing much more sinister and racist. The meme of “Joe and the Hoe” employs misogynoir, while other memes falsely claim that Harris is not a Black American. Similar racist tropes and birther conspiracies were deployed against Harris during the Democratic primary, but after she backed out of the race, not much new content was created. Democratic voters seem unphased, as they have not significantly picked up the outrage content, nor have they shared it through their networks. Instead, the most vitriolic memes seem to be stuck in the iron cages of Trump-supporting echo chambers.

Like Grumpy Cat, if content is truly memetic it will re-emerge in different ways. Lighter fare, like this video of the “Trump Train” picking up steam while Joe Biden lags behind, did enjoy some viral distribution, but after a copyright violation claim, few copies remain online. The Trump Train is a consistent feature on social media, where Trump fans will use the hashtag to call attention to content that should be shared. Using #TrumpTrain, the president’s supporters have created extensive follower networks that are agile in curating content that eventually finds its way into Trump’s orbit.

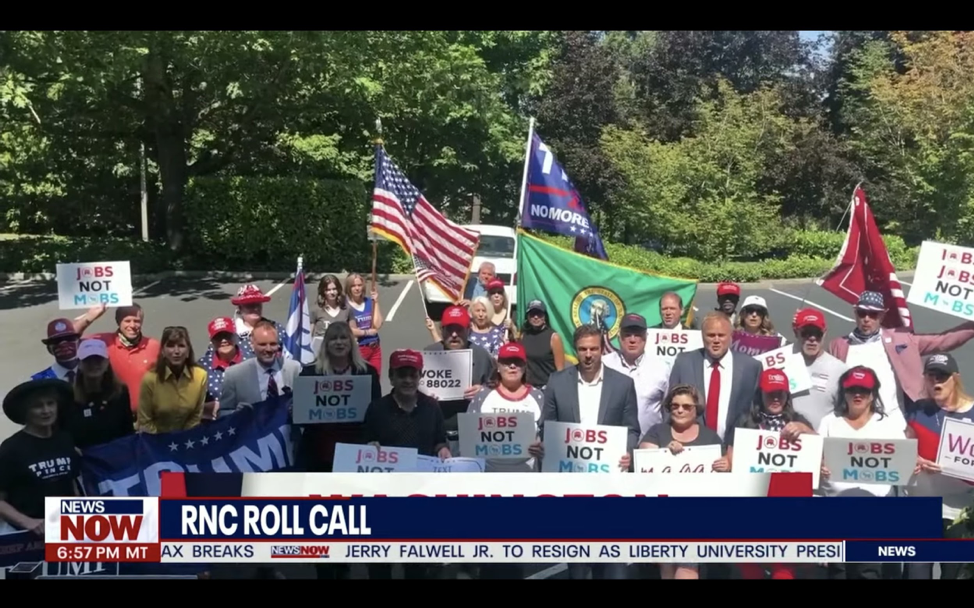

For example, in 2018, the New York Times traced how the “Jobs Not Mobs” slogan traveled across the web and social media before Trump used it. The “Trump Train” was early to spread this meme, and most recently, a group pictured in the Republican National Convention roll call were all holding signs with this viral slogan.

Returning to the video of Biden (supposedly) grooving to N.W.A, a meme can become disinformation, not because of its content, but because of a change in its context. While the video was a meme when it was circulating through accounts without much clout, when someone in power like the president shares it, the stakes change dramatically. As CNN recently pointed out, “Trump’s use of false content is often defended as humor. But his supporters aren’t always in on the joke.” In this investigative piece, Donie O’Sullivan attends a Trump rally to assess the degree to which rally-goers believe disinformation. Even when confronted with fact-checks, individuals remember memes because they have produced a positive emotional response and a sense of belonging. Taken together, this creates a treacherous terrain to carry out an election, where the line between likes and lies is razor thin.

As the election looms, more targeted memetic warfare techniques will arise and find a home in campaign materials. Some will come from a candidate’s staff and others from super PACs or dark money groups. And yet, many will come from everyday folks, remixing images with pithy slogans in an attempt to impress or troll friends, colleagues, and fellow travelers. If they’re lucky, their favorite politician might even give it a share.

[1] Editor’s note: Reid Hoffman is a funder of MediaWell.