The following is an essay written by a SSRC Social Data Research Fellow, based on their project. The program was generously funded by the Omidiyar Network.

The 2020 presidential election cycle highlighted the critical role that local election officials—the over 8000 public servants tasked with running elections in the United States—play in educating the public about what is needed to vote and how elections are run. Changes made to ensure voters were able to cast ballots safely without jeopardizing their health, such as the widespread adoption of mail-in voting, meant that election officials had the monumental task of not only implementing these changes, but informing prospective voters how to take advantage of them.

The importance of voters having trustworthy, accurate sources of information about elections and how to vote has grown in recent decades alongside rising mis- and dis-information and decades of decline in public confidence in the administration of elections. My research is focused on the question of what can be done to help ensure Americans have the information needed to cast a ballot. When Americans know more about the electoral process, they have greater confidence in election outcomes and are more likely to participate. On the other hand, Americans’ willingness to trust and engage in democracy erodes when they lack information about what is needed to vote and are disenfranchised as a result.

To address this, my research focuses on U.S. local election officials’ use online resources—social media platforms and websites—to provide information to their constituents about how to vote. I focus on local election officials because the public has maintained relatively high levels of confidence in these officials, making them well positioned as trusted sources of information about elections. Additionally, I focus on online efforts because the public tends to seek information about how to vote online, and mis-and dis-information about elections that can be sources of confusion are widely spread in online spaces. In short, cataloguing the online accessibility of voter education from local election officials is an important baseline for understanding voter education in the United States.

To study voter education efforts online, I conducted a search for the official webpages and social media accounts across Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for every local election office in the United States—over 6000—and conducted a content analysis of social media posts for a sample of jurisdictions, including over 10,000 posts shared by local election officials in the state of Florida of during the 2020 election cycle, and nearly 2000 posts shared by officials in the state of North Carolina.

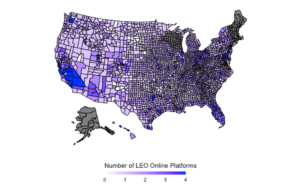

There is significant variation in the online availability of information about how to vote. Figure 1 is a map of where these local election officials have an active website or social media presence across all county-level jurisdictions in the United States. The darkest colors show counties where local election officials (LEOs) have a presence across all four platforms—including an active website—and lighter colors show where they have a presence across fewer platforms. Websites are by far the most commonly available resources for voters; about 89% of counties had an active webpage with at least some information about elections.[1] The most popular social media platform by far was Facebook; about 33% of counties had an active Facebook account for voter education during the 2020 presidential election. Only 9% had active Twitter accounts, and only 2% had active Instagram accounts.

Figure 1: Where Are Local Election Officials Active Online?

The map illustrates where there are gaps in voter information available online from county election officials. These gaps follow some notable patterns: communities with higher percentages of constituents without an undergraduate degree and with more low-income constituents are less likely to have a local election office with a robust online presence. At the same time, counties that have colleges and universities, and are situated in states that are regularly considered battlegrounds in presidential elections, are more likely to have a local election official that is active across multiple online platforms. Finally, counties where a higher percentage of voters tend to cast ballots for Democratic presidential candidates are also more likely to have an election office active in providing information across multiple platforms.

Ultimately, these differences suggest that voter education efforts may be lacking where communities need it most. People in low-income communities, and less-educated people, may not have the resources to navigate the sometimes-complex bureaucratic processes required for voting. That local election officials are more active where there is more electoral competition suggests they may be attuned to ensuring their voters are well-informed given the prospect of increased scrutiny during a close presidential election. Voters living in counties situated in “safe” states during presidential elections—although they require the same information as voters in more competitive environments—are nevertheless not as likely to encounter voting information online from their local election officials. Finally, the fact that counties with greater support for Democratic presidential candidates are more likely to have local election officials who actively provide information about elections online is an especially concerning pattern given that Republicans were far more likely to not trust that their ballot was counted as intended and more likely to believe in the false claims that the 2020 Presidential election was stolen from then-President Donald Trump.

Despite significant gaps in the availability of online information about elections from local election officials across the United States, my research also shows that, where robust, these efforts do have an impact on voter behavior. Florida election officials who shared content about voter registration on their Facebook accounts saw greater use of Florida’s online voter registration system by their constituents, and higher rates of new registrations. And those who were more active in promoting mail voting on Facebook saw lower rates of mail ballots that were rejected for mistakes or being late. Similarly, in North Carolina, where local election officials prioritized content about how to vote by mail, individuals were more likely to cast a valid mail ballot that was accepted.

As the United States moves forward from the pandemic and misinformation-tinged 2020 presidential election, local election officials will need to continue to make concerted efforts to inform voters about how to vote and to be transparent about how they administer elections. The variation in online voter education uncovered by my research raises concerns about the extent to which eligible voters have equitable access to information about elections in different jurisdictions across the United States. It also shows the real potential of local election officials’ efforts to educate voters, highlighting the importance online voter education to improve access to voting. These efforts will be especially vital in the midst of significant rollbacks to voting rights being enacted in state legislatures across the country that further threaten access to the ballot; without federal protections and legislation preserving voting rights, this access will be dependent, in large part, on the ability of local election officials to inform their constituents about how to navigate changes to voting requirements through voter education.

The views expressed in this essay are the author’s own and not the Social Science Research Council’s.

[1] There are select states—Wisconsin and many New England States—where elections are run at the municipal level. Data for local election official online presence in these jurisdictions are not included in this map.