Abstract:

Recent trends of migration to smaller social media platforms among right wing actors have raised a caution that an excessive focus on large, transnational social media companies might lose sight of the volatile spaces of homegrown and niche platforms, which have begun to offer diverse “alternative” avenues to extreme speech. Such trends, which drew global media attention during Trump supporters’ attempted exodus to Parler, are also gaining salience in Europe and the global South. Turning the focus to these developments, this article pries open three pertinent features of extreme speech on small platforms: its propensity to migrate between platforms, its embeddedness in domestic regulatory and technological innovations, and its evolving role in facilitating hateful language and disinformation in and through deep trust-based networks. Rather than assuming that smaller platforms are on an obvious trajectory toward progressive alternatives, their diverse entanglements with exclusionary extreme speech, I suggest, should be an important focal point for policy measures.

Earlier this year, in India, following Twitter’s decision to take action against exclusionary extreme speech on its platform by blocking several handles, religious majoritarian voices rushed to the Koo app, a homegrown platform founded in March 2020. Pro-government television channels promoted Koo as “the best Twitter alternative for Indians” and publicized the so-called “trending hashtags” on the new app. The attempted exodus of Trump supporters to the self-styled free speech platform Parler made headlines globally, but right-wing actors in Brazil tried to migrate, more quietly, to the same platform in 2020. With their resonating forms of multimodal content, platforms such as IMO, Likee, and Vskit are expanding in Kenya, prompting internet watchdogs to take note of their potential political fallout (Wamuyu 2020). These recent trends raise a caution that an excessive focus on large, transnational social media companies might lose sight of the volatile spaces of homegrown and niche platforms that have begun to shape political discourse by offering diverse “alternative” avenues for public expression and exchange.

For some years now, the vast reach of transnational social media platforms and the ways they amplify, curate, and co-create exclusionary extreme speech[1] have been the focal point of critical scholarship and regulatory discussions around digital communication. Understandably, much of the focus is concentrated on the “Big Three”—YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter—and their subsidiaries. Studies have parsed platform complicity in terms of the potential of recommendation algorithms to isolate users in ideological content bubbles, as well as in terms of interface designs that augment rhetorical strategies to “emotionalize” exclusionary discourses. For instance, researchers have argued that social media platforms like YouTube can draw users into an algorithmically sustained extreme-right ideological bubble after just a few clicks (Lewis 2018). Studies have also highlighted the role of advertisement policies that allow funded disinformation campaigns and the general feel and texture of the platforms, which embed distinct kinds of user practice and collective actions rife with violent possibilities. The anthropologist Meg Stalcup (2016), for example, has drawn attention to how the platform aesthetics of WhatsApp and their political deployment have facilitated fake news circulation in Brazil. Regulatory efforts have formalized the emphasis on large social media companies through the principle of proportionality and have imposed more severe obligations on “very large platforms,” defined as “systemic platforms” in recent regulations such as the European Union’s (EU) proposed Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act. While regulatory actions and scholarly attention around the Big Three are no doubt justified, several important trends test the limits of centering big platforms in critical inquiries.

Across the global North and the South, platforms that are homegrown, niche, or simply smaller than the Big Three are slowly but surely expanding. Such platforms are small in a direct sense of having a smaller user base—below 10 percent of the national population, to follow the benchmark used by the EU Digital Services Act—but also in the more discursive sense of being relatively small vis-à-vis transnational big platforms in political and media framing. A simple heuristic might be to delineate small platforms as a negative category—those that remain after eliminating the Big Three, and those that are neither acquired by the Big Three nor part of the “dark web.” The platforms that fall into this category can take a variety of forms. Typically, such platforms are more regional language friendly, and more aligned with local cultural and political repertoire. As is the case with VKontakte (VK), described as “Russian Facebook,” in Germany, there are also instances where small platforms are “foreign players” that brandish free speech values to promise lax site policing. Another emergent variety is “alternative social media” such as Mastodon, which offers “federated” microblogging system with open-source protocols (Zulli, Liu, and Gehl 2020). Mastodon describes itself as an “open source decentralized…community owned, ad-free…social network,” where users are not drawn into a single website (run by a single company) but have the option of forming communities by running their own open-source-based servers.

Studies have argued that the decentralizing architecture of Mastodon-type smaller platforms has the potential to enable progressive alternative discourses and community autonomy, in contrast to corporate social media’s “layers of abstraction and centralization that eliminate users from decision-making processes” (Zulli, Liu, and Gehl 2020, 1188). However, there are also growing concerns that hateful language has found a new home on smaller platforms by becoming migratory, fleeting, coded, and suggestive (Ganesh 2018; Gaudette et al. 2020; Myagkov 2020; Rogers 2020; sCAN 2019).

Migratory speech

In a first-of-its-kind survey, the EU-funded project sCAN observed that the predominance of the Big Three tech firms “is no longer uncontested” in the social networking domain. Aside from the reported “big platform fatigue” among younger users, the growing uptake for small platforms comes from the promise of lax regulatory attention and enforcement. The report lists VK, Tumblr, and Gab as platforms that are “popular with right-wing extremists and far-right actors” who are active in spreading “racism, antisemitism, homophobia, and hate speech against refugees and Muslims” (sCAN 2019). Gab, for instance, drew media attention when the shooter who attacked a synagogue in Pittsburgh in October 2018 made an announcement about the attack on the platform. Similarly, the sCAN report noted that the content takedown rate following complaints of illegal speech is disappointingly low at VK.

The sCAN report examined the cases in Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, and Slovenia, but media commentaries and a handful of scholarly studies have found similar trends elsewhere with different degrees of intensity and diverse features developed in response to a mix of regionally distinct factors. A cross-cutting pattern, however, is the itinerant and migratory nature of extreme speech and disinformation that precipitate around small platforms at various intervals. This migratory nature is largely driven by online users who actually hop between the platforms, but studies have also established the “mesoscopic dynamics” of social clusters that are distributed across social media platforms (Johnson et al. 2018). As Neil F. Johnson and colleagues have demonstrated, problematic speech can acquire velocity and capacity to sustain partly through modifications to its linguistic features as it travels across “multiplatform hate highways” linking clusters of users, from “the local, to national and the international level” (Johnson et al. 2018, 3).

Alt-right conservatives and other extreme-speech actors have used or repurposed smaller platforms by hopping into and between them to avoid the regulatory gaze. In a recent study, Richard Rogers has shown that anti-establishment right-wing celebrities in Europe migrated to Telegram and to a “larger alternative social media ecology” after being “deplatformed” by major social media companies including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube for “offenses such as organized hate” (Rogers 2020, 213). The network graphs that mapped the connections between right-wing celebrities and platforms revealed the prominence of BitChute (an alternative to YouTube), Minds (an alternative to Facebook), Gab (an alternative to Twitter) and Telegram (the hybrid messaging and broadcasting platform) (Rogers 2020, 219; see also Myagkov et al. 2020). Faced with regulatory actions, violent Jihadi groups similarly moved to encrypted channels such as Telegram and file-sharing sites such as Pastebin. [2]

Such migratory moves draw upon and mobilize niche formats of toxic mashups and playful interactional frames that characterize smaller platforms such as 4chan. Often, right-wing users utilize large social media platforms to decry actions against them and “announce” their migration to smaller platforms, urging other users to follow them. Migratory moves around extreme speech are also embedded within multilayered recruitment strategies spread across platforms of varied sizes and appeal. The sCAN report noted, for instance, how Instagram is used as an “eye catcher to establish first content with subtle propaganda…[and] from there, followers of extremist profiles are linked to more explicit and violent content on platforms with a more lenient stance towards hate speech” (sCAN 2019). Users employing such strategies have keenly followed the distinctive protocols and features of different platforms, devising ways to reach out to potential communities by exploiting uneven content moderation policies across companies.

Localized innovations

If migratory speech is a salient feature of extreme forms of communication on small platforms, the picture is further complicated by the susceptibility of small platforms to political manipulations and polarized content—a trend increasingly observed in the “global South” context. A combination of influencing factors has led to this scenario. Small platforms are expanding in the midst of market competition for digital technology enterprise that has now extended to “data tested” election campaign management as a new field of business opportunity. In India, smaller social media platforms are growing not only by drawing domestic capital but also through technology innovation, imitation, and repurposing. For instance, “Tooter,” a new and very small Indian social media platform, was built from Gab’s Mastodon-based code. The US-dominated Gab and the decentralized architecture of Mastodon, built in Germany, ironically facilitated Tooter’s claim that it was “swadeshi”—a politically loaded assertion that it is an indigenous and self-reliant enterprise. The ideology of “national” tech enterprise shaped by the postcolonial politics of national self-reliance and the simultaneous pressures to be tech-ready in the global marketplace have emerged in the wake of three decades of economic reforms in India, when information technology (IT) became the torchbearer for the country’s foray into the global high-tech economy. During this same period, Silicon Valley entrepreneurial zeal spawned by tech outsourcing created a domestic class of IT entrepreneurs competing to innovate for market gains (see Upadhya 2016; Udupa 2015).

Shaped as such by technology-led market competition and celebratory uptake for technological innovation, use of small platforms by political actors, however, reveals an intriguing space. Small platforms are enmeshed with, if not captured by, shadow networks of clickbait operators and digital amplifiers that politicians and even ruling regimes engage to spread electoral propaganda. Backed with regional-language reach, several small startups in India have allowed their platforms during the election times to serve as channels for partisan messaging and manipulations through intricate networks of lobbying and buyouts, or because of the sheer pressure to stay in business. They have also sought to profit from platform migration when users, faced with blocking and other content moderation actions, leave large social media companies in search of unmoderated platforms. Some of the executives of such companies also double up as campaign management specialists for resource-rich politicians. While not all of them directly monetize extreme speech and some of them do indeed highlight the value of open, bottom-up discourses, it is important to monitor how such platforms are evolving.

Aside from Koo, which offers services in English and five Indian languages and claims six million downloads of its app, the startup ShareChat currently has 160 million monthly active users and operates in 15 Indian languages and not in English. ShareChat’s opaque content moderation policies and lack of regular transparency reports (except during the 2019 general elections in India) have raised concerns about unregulated circulation of problematic speech on its platform. In 2020, ShareChat launched the short-video platform “Moj” only days after TikTok was banned in India. Moj’s terms of use mentions that the company “may share [user] information with appropriate law enforcement authorities if [they] have good-faith belief that it is reasonably necessary to share your personal data or information in order to comply with any legal obligation or any government request.” In the context of tighter regulatory controls over online discourse, such terms of use ingrained in homegrown startups could contribute to further restrictions on open and critical public debate. For instance, Twitter and WhatsApp have openly resisted the Indian government’s new internet intermediary rules, which, among other things, mandate large platforms to retain user data and provide them to state authorities, when requested, to ensure “traceability of communications.” Koo, on the other hand, was one of the earliest to confirm that it had met the requirements, declaring that its swift compliance with the Indian governmental regulations “shows why it’s important to have Indian social media players thriving in the country.” Such declarations signal the tendency of small platforms to adhere more strongly to the regulatory directions of domestic governments than to the spirit of international human rights standards or (still evolving) global frameworks for platform governance. What’s more, French ethical hacker Robert Baptiste cautioned that users of small platforms such as Koo are highly vulnerable to data breaches, as he was able to easily access personal data of users—a charge that the company vehemently denied.

Deep extreme speech

Arguably, the most serious dimension of small platform expansion in the larger context of digital mediation of political discourse is its evolving role in what I describe as deep extreme speech. If online extreme speech circulation is driven in part by technological features of virality and algorithmic mediation, a significant part of this circulation operates by tapping social trust and cultural capital at community levels, often making deep inroads into the “intimate sphere” of families, kin networks, neighbors, caste-based groups, ethnic groups, and other long-standing social allegiances. Such types of vitriol rely on and rework localized community trust as the key lubricant for the networked pipeline of hate and hate-based disinformation.

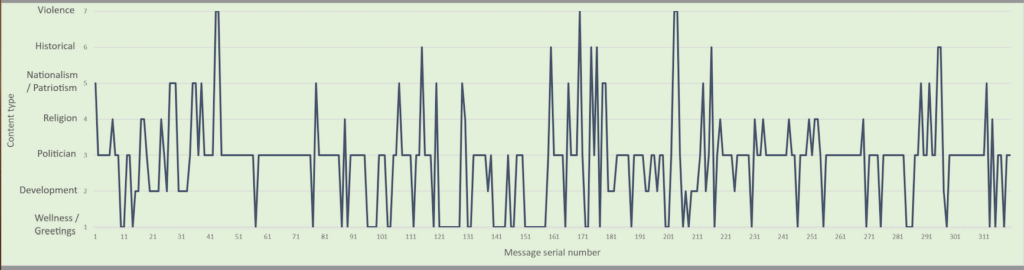

In India, WhatsApp has so far been the primary conduit and site for deep extreme speech. Across urban and rural India, WhatsApp is hewn and hammered to create intrusive channels for inflamed rhetoric of different kinds. Expressions that circulate in these networks can be coded, in the sense of requiring relevant cultural knowledge to make sense of them, but they can also contain direct forms of hateful language. Political parties have remodeled WhatsApp to serve a heady concoction of top-down “broadcasts” and “organic bottom-up messaging” by installing “party men” within WhatsApp groups of family members, friends, colleagues, neighbors, and other trusted communities. “WhatsApp penetration”—defined as the extent to which party people “organically” embed themselves within trusted WhatsApp groups—is seen as a benchmark for a political party’s community reach. Local musicians, poets, cinema stars, and other “community influencers” have been recruited to develop and expand such “organic” social media networks for party propaganda. These tactics have been especially pronounced in the case of the right-wing ruling party but they are also seen among other major political parties that are increasingly investing in digital campaigns. Typically, a party moderator would find his way into a WhatsApp group through local connections or by leveraging community work such as local brokerage to help people to access state benefits and so on. Once admitted, he would relay party messages in unobtrusive ways, often embellished with jokes, good morning greetings, religious hymns, microlocal municipal issues, and other kinds of socially vetted and existentially relevant content. The temporal flow of such messages—amplified and articulated by ordinary users—is characterized by sudden appearance of explicitly hateful messages against Muslims in the midst of an otherwise benign sequence of pleasant or “caring” messages (see Figure 1).[3] The flow of content thus simulates the lived rhythm of the social.

Deep extreme speech that works its way through intimate channels of kin and kin-like relations amid a tactical mix of content might be seen as the social corollary for technologized deep fakes and commercial digital influence services. Analytically distinct but intermingled in practice, these forms are reconfiguring, rather than dismantling, structures of trust in political discourse. By centering community allegiances in the distribution logics, such forms have placed extreme speech at the confluence of affect and obligation, thereby delinking it from the impersonal constructions of truthfulness or moral constructions of hatred. In other words, when messages are embedded within personalized, trust-based networks, what ensues is not as much a problem of truth (whether it is true or false) or the problem of morality (whether it is good or bad) but an emotional or obligatory urge to share them and be in (if not with) the flow.

The affective dimension of extreme speech, for instance, is starkly evidenced by the fun cultures of online exchange when people who peddle exclusionary discourse take pleasure and celebrate their collective aggression (Udupa 2019). Internet memes present a vivid example of hilarity as a means for hatred. Equally, the satisfaction of trending something online speaks to how right-wing actors draw fun from seeing their posts gaining traction and “scoring” against their ideological rivals. I have argued that digital fun cultures embed distance and deniablity in ways that enable right-wing actors to evade the moral and regulatory gaze by framing their extreme expressions as “merely funny” or by experiencing the fun of aggression by drawing strength from one another in a collective paticipatory culture. In the context of deep extreme speech, fun cultures are amplified by social trust and the familiar language of in-group exchange. The aspect of obligation is pronounced in the case of deep extreme speech, as users within kin or kin-like networks feel the need to share and respond to the messages they receive. Any form of inaction on received content conflicts with the sense of obligatory ties and reciprocity that define socially thick networks of deep extreme speech. In such circulatory milieus, responsible action is itself conceived as circulation—the sense that by forwarding the messages one has done one’s duty (Udupa 2019, 190–205).

While WhatsApp is still a key conduit for deep extreme speech, and for this reason research should continue to uncover its manifold impacts, regional-language-friendly smaller platforms are emerging as alternative spaces, especially after large platforms entered into tense battles with the Indian government over content takedowns and moderation.

Policy for the fringes

The intricate networks through which online extreme speech circulates in a shifting regulatory climate and the growing role of smaller platforms in this mix stress the need for policy measures that go beyond the assumption that regulatory control over big social media companies would solve a complex social and political-economic problem. The EU framework, for instance, has premised that breaking open the “centralized platform economy” comprising big transnational corporates, would significantly reduce the conditions of virality and amplification of online illegal content. In contrast to (justified) suspicion toward the Big Three, the EU Digital Services Act has highlighted the potentiality of small platforms to offer a space for alternative discourses that could provide a more level playing field in the “marketplace of ideas.” The principle of proportionality elaborated in these regulations has linked the pursuit of anticompetition policy objectives with the assumption that small platforms hold the possibility to push back against the Big Three’s monopoly over online discourse.

Although the EU proposal to require very large platforms (Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube) to open up to competitors with mandatory interoperability is relevant in the pursuit of anticompetition policy objectives, this is not an obvious solution to the problem of extreme speech. This proposal assumes that regulating large platforms and fostering smaller players would create a scenario where “users could freely choose which social media community they would like to be part of—for example depending on their content moderation preferences and privacy needs—while still being able to connect with and talk to all of their social friends and contacts” (EDRi 2020, 4). This approach, thick with liberal baggage, underestimates the possibility that this very “marketplace for ideas” could provide an easy way for hate mongers—as illustrated by alt-right actors—to hop between platforms and innovate on content. Even more, as emerging scenarios in India suggest, politically vested interest groups are likely to invest and drive the market of multiple smaller players toward partisan and divisive messaging. The proposal for interoperability, in other words, should be combined with a host of other measures to address proxy campaigning and shadow politics of digital manipulations. In several cases of repressive and authoritarian conditions, global corporations with some stable moderation practices and resources have been more responsive to implementing safeguards against extreme speech and illegal content than the sundry mix of unregulated platforms that operate in the gray zones (see Ong 2021). Although such maneuvering raises the risk of framing “corporate capital as an explicit ally in the struggle for a just world” (Flood 2019), what is argued here is that the risks of small platforms—many of which are equally capitalized—require some hardheaded policy actions.

Policy measures should recognize that while large multinational social media companies play a major role in the amplification, curation, and distribution of extreme speech, critical attention is necessary to track how smaller and niche platforms have emerged as a breeding ground for hateful subcultures, as alternative venues and transit points for “mainstream” hate, or as the gray zones for deep extreme speech. Especially in contexts where governments are coming down hard on the Big Three for not complying with their repressive regulations, domestic platforms that use improvised, patchwork technologies with backhanded backing of the ruling regimes can become the new danger zone.

Rather than assuming that smaller platforms are on an obvious trajectory to becoming progressive alternatives, policy measures should focus on such platforms’ diverse entanglements with exclusionary extreme speech. Without scuttling the growth of small platforms with resource-heavy compliance requirements or writing off their potentiality for inclusive narratives of public value, regulatory actions should nonetheless mandate periodic transparency reports on advertisement policy, content moderation practices, and the use of artificial intelligence/automated decisions, including algorithmically mediated recommendation systems, if any. It is crucial for policy measures to involve cross-platform monitoring of extreme speech to track platform migration and the particular role of small platforms in offering transit repositories for problematic handles and content. Policy actions should also concentrate on ramping up natural language processing models that can detect and demote exclusionary extreme speech in diverse regional languages that smaller platforms are building capacities for. The EU’s policy measure to promote “trusted flaggers” to expedite the process of notices, complaints, and removal of illegal content should be strengthened to cover smaller platforms, and such structures of public accountability should be implemented in countries where small platforms are expanding. This system, aimed at strengthening community involvement, requires platforms to act on priority when credible organizations with the “trust flagger” status report problematic content.

Such proposed policy measures also prompt us to reflect on the slants and emphases in current thinking. While studies should continue to interrogate the vast reach and colossal presence of big platforms, the assumption around their “centralizing control” might no longer be an adequate conceptual approach. Critical discussions around digital communication should move beyond the conceptual language of the centralizing Big Three and sharpen the focus on digital practices that are evolving at the nexus of microenterprise, localized political innovation, and migratory speech. It is time to look to the “fringes” as imminent and consequential fields that could realign or amplify the mainstream discourse and portend what is to come.

This article is based on the commissioned research paper,“Digital Media and Extreme Speech: Approaches to Counter Online Hate” for the United Nations Peacekeeping Technology Strategy. You can access the full research paper here.

**

[1] “Extreme speech” refers to speech acts that stretch the boundaries of legitimate speech along the twin axes of truth/falsity and civility/incivility. Extreme speech can be progressive or regressive depending on the context (speaker, target, technology and historical conditions). “Exclusionary extreme speech” refers specifically to expressions that call for or imply exclusion of vulnerable and historically disadvantaged communities (see Udupa 2021 for the definitions of derogatory extreme speech and exclusionary extreme speech).

[2] Ganesh (2018) has argued that three formal features of digital hate cultures make them ungovernable: swarm structure characterized by decentralized networks; exploitation of inconsistencies in web governance between different social media companies as well as between private and government actors that allows hate content to migrate when detected; and the use of coded language to evade content moderation.

[3] See Alan Finlayson (2020) for a similar rhetoric of care and “therapeutic benefits” that alt-right ideologues promise their supporters online.

[workscited]EDRi. 2020. “Platform Regulation Done Right.” EDRi Position Paper on the EU Digital Services Act, European Digital Rights, Brussels.

Finlayson, Alan. 2020. “YouTube and Political Ideologies: Technology, Populism and Rhetoric.” Political Studies, July 14, 2020. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0032321720934630.

Ganesh, Bharath. 2018. “The Ungovernability of Digital Hate Culture.” Journal of International Affairs 71 (2): 30–49.

Gaudette, Tiana, Ryan Scrivens, Garth Davies, and Richard Frank. 2020. “Upvoting Extremism: Collective Identity Formation and the Extreme Right on Reddit.” New Media and Society, Online fir: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820958123.

Johnson, Neil F., Richard M. Leah, N. Johnson Restrepo, Nicolás Velásquez, Minzhang Zheng, Pedro D. Manrique. 2018. “Social Media Cluster Dynamics Create Resilient Global Hate Highways.” https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.03590v1.

Lewis, Rebecca. 2018. Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube. New York, NY: Data & Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DS_Alternative_Influence.pdf.

Myagkov, Mikhail, Evgeniy V Shchekotin, Sergey I Chudinov, and Vyacheslav L. Goiko. 2020. “A Comparative Analysis of Right-Wing Radical and Islamist Communities’ Strategies for Survival in Social Networks (Evidence from the Russian Social Network VKontakte).” Media, War & Conflict 13 (4): 425–47.

Ong, Jonathan. 2021. “Southeast Asia’s Disinformation Crisis: Where the State Is the Biggest Bad Actor and Regulation Is a Bad Word,” Items, Social Science Research Council. https://items.ssrc.org/disinformation-democracy-and-conflict-prevention/southeast-asias-disinformation-crisis-where-the-state-is-the-biggest-bad-actor-and-regulation-is-a-bad-word/.

Rogers, Richard. 2020. “Deplatforming: Following Extreme Internet Celebrities to Telegram and Alternative Social Media.” European Journal of Communication 35 (3): 213–29.

sCAN. 2019. Beyond the ‘Big Three’: Alternative Platforms for Online Hate Speech. Brussells: European Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme. https://www.voxpol.eu/download/report/Beyond-the-Big-Three-Alternative-platforms-for-online-hate-speech.pdf.

Stalcup, Meg. 2016. “The Aesthetic Politics of Unfinished Media: New Media Activism in Brazil.” Visual Anthropology Review 32 (2): 144–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12106.

Udupa, S. 2017. “Viral Video: Mobile Media, Riot, and Religious Politics.” In Media as Politics in South Asia, edited by S. Udupa and S. McDowell. London: Routledge.

Udupa, Sahana. 2015. Making News in Global India: News, Publics, Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Udupa, Sahana. 2019. “Nationalism in the Digital Age: Fun as a Metapractice of Extreme Speech,” International Journal of Communication 13:3143–63. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/9105.

Udupa, Sahana, 2021. “Strategy Paper on Extreme Speech and Digital Technology,” United Nations Department of Peace Operations.

Upadhya, Carol. 2016. Reeingineering India: Work, Capital and Class in an Offshore Economy. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Wamuyu, P. K. 2020. The Kenyan Social Media Landscape: Trends and Emerging Narratives, 2020. Nairobi: SIMElab. https://www.usiu.ac.ke/assets/image/Kenya_Social_Media_Lanscape_Report_2020.pdf.

Zulli, Diana, Miao Liu, and Robert Gehl. 2020. “Rethinking the ‘Social’ in ‘Social Media’: Insights into Topology, Abstraction, and Scale on the Mastodon Social Network.” New Media and Society 22 (7): 1188–1205.

[/workscited]