Motivation: Why Fact-Checking Alone Fails Teenagers

During a high school workshop on misinformation I recently led, a student said something that stuck with me: “If it’s funny, I share it.” He was not being sarcastic or malicious; he was being honest. And he was not the only one. What surprised me even more was that many of these students already knew how to identify misinformation and use fact-checking tools.

Yet despite having the skills, they still shared misinformation. Why? Because sharing didn’t feel harmful. For many teens, the consequences of misinformation seem abstract—something that affects others, not themselves. What’s often missing isn’t knowledge—it’s empathetic concern. And a lack of empathy can be just as dangerous as believing misinformation.

This is where social and emotional learning (SEL)—especially the development of empathy—can make a critical difference. My research explores how integrating SEL into media literacy education can encourage teenagers to reflect ethically on their digital behavior.

Reframing the Problem: Misinformation as a Social, Not Just Informational Issue

For years, media and information literacy (MIL) has served as the primary educational response to misinformation. These programs teach students how to assess credibility, verify facts, and recognize bias (Wilson et al. 2011). Tools like the “SFIT” method or the “How to Spot the Fake News” checklist offer clear steps for evaluating online content (Eva and Shea 2018).

While these skills are vital, they fall short in today’s media ecosystem—especially for teenagers. Teens often consume news through social media and are more likely to trust influencers, celebrities, or peers than traditional media sources (Howard et al. 2021). They may share posts not because they believe them, but because they’re funny, shocking, or help gain social approval (Herrero-Diz et al. 2020). In such moments, humor and peer validation often override critical thinking (Figueira and Oliveira 2017; Herrero-Diz et al. 2020; Loos et al. 2018).

The “Tide Pod Challenge” is a stark example. Teens knew that eating detergent pods was dangerous and that claims like “Tide Pods taste like candy” were misinformation. But the challenge went viral—not out of belief, but because it was funny, and attention-grabbing. What started as a joke became a harmful trend with real-world consequences (McCarthy 2018). The issue wasn’t a lack of knowledge, but the social dynamics that encouraged risky behavior.

MIL programs often treat misinformation as a technical problem solvable by better tools or sharper skepticism. But they rarely address why misinformation resonates with teens, how it spreads socially, or what ethical responsibilities young people carry (Mihailidis and Viotty 2017). To be effective, we should confront misinformation as a deeply social and emotional phenomenon—one shaped by teens’ relationships, identities, and lived experiences.

A Shift in Perspective: Teenagers as Misinformation Creators and Amplifiers

Teenagers today are not merely passive consumers of online content—they are active creators, remixers, and amplifiers (Marwick and Boyd 2014). According to the Social Media and Youth Mental Health report (2023), up to 95% of teens use social media, with more than a third using it “almost constantly.” Through platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube, teens play a central role in shaping what others see and believe—whether by posting, resharing, or boosting viral trends (Howard et al. 2021).

Yet many do not see themselves as responsible for what they share. They often view misinformation as someone else’s problem. This disconnection—known as third-person effect—creates a troubling situation where teens have the power to shape what others see online but don’t recognize the responsibility that comes with that power (Corbu et al. 2022).

To bridge this gap, we must frame misinformation as not just an accuracy issue but a social and emotional one. We must help teens see misinformation as something that can harm relationships, reputations, communities—and themselves. This starts by shifting the goal of education from correcting mistakes to fostering responsibility.

Empathy in Action: Integrating SEL into Misinformation Education

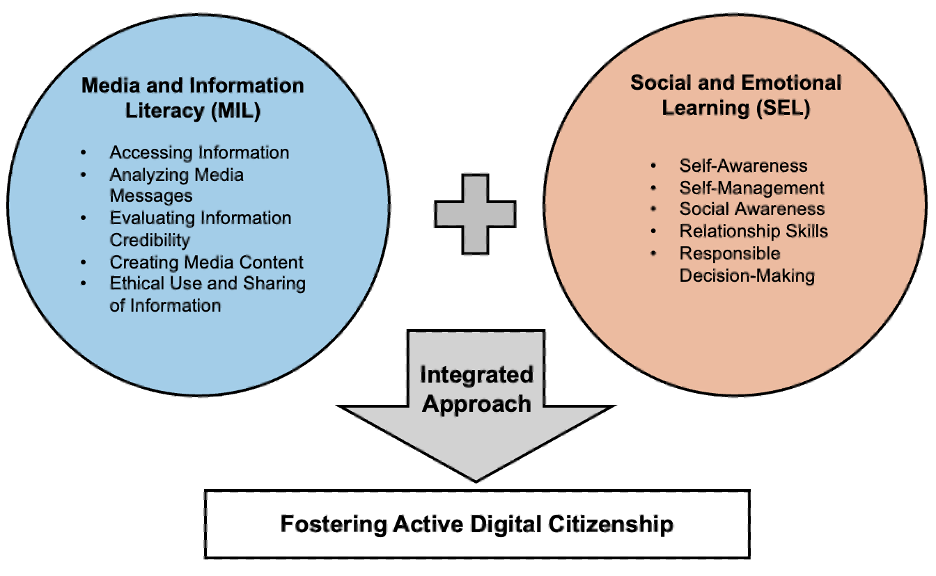

Social and emotional learning (SEL) offers a powerful framework for reimagining misinformation education. It builds five core competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making (CASEL 2015). When integrated with media and information literacy (MIL), these competencies do more than enhance critical thinking—they help cultivate ethical, reflective, and compassionate digital citizens (see Figure 1).

To apply this framework in practice, I developed and implemented an SEL-based misinformation learning module composed of a game and a structured debriefing session. The game—ChronoShift Reality Rewritten—was created at the University of Washington and situates players in a fictional high school election disrupted by a digitally manipulated image. Participants encounter five distinct roles, each representing a part of the misinformation ecosystem:

- Misinformation Producer: unintentionally creates a fake image using AI.

- Misinformation Sharer: circulates the image without verification.

- Misinformation Influencer: amplifies content across social media platforms.

- Disinformation Producer: intentionally creates harmful deepfake content.

- Misinformation Victim: suffers reputational harm as the misinformation spreads.

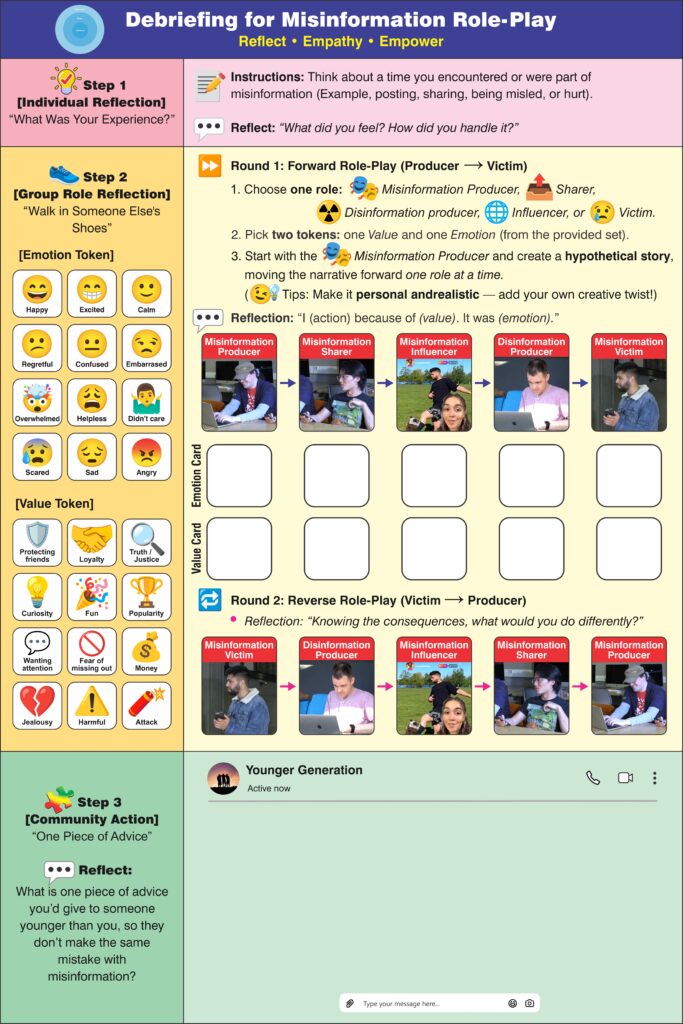

Players navigate escape room-style puzzles in teams, requiring them to collaborate and reflect. After gameplay, they participate in a structured debriefing session using a SEL-based debriefing board I designed (see figure 2). This board uses role-play and guided questions—such as “Why did you share that?” and “How might someone else feel if they saw this?”—to prompt emotional and ethical reflection (Marathe and Sen 2021).

The SEL-based debriefing board supports participants in reflecting emotionally and ethically after role-playing misinformation scenarios in the ChronoShift game. Guided questions encourage teens to consider their digital behaviors’ emotional and social impacts.

Source: Adapted from ChronoShift Reality Rewritten misinformation game, developed at the University of Washington. © University of Washington. Used with permission.

Drawing from evidence-based SEL practices, role-play helps students step into others’ perspectives, deepening their understanding of the emotional and social impact of their actions (Dewi et al. 2020; Mahmoud 2024). This approach builds empathy, strengthens ethical decision-making, and fosters inclusive peer relationships (Dallacqua et al. 2022).

Although data collection is ongoing, preliminary reflections from students suggest that combining gameplay, role-play, and emotional inquiry helps them move beyond abstract concepts of “true vs. false” and toward a more relational understanding of their online behaviors.

Conclusion: Rethinking What We Teach About Misinformation

We often teach young people how to decode information but rarely teach them how to pause, relate, and decide with care. That decision—whether to share something, how to respond to a post, or how to represent themselves online—is at the heart of digital responsibility. Misinformation education cannot stop at accuracy; it must reach into how teens interpret, feel about, and respond to the world around them. Empathy offers a quiet-but-transformative shift: from reacting to reflecting, from scrolling past harm to stepping into someone else’s shoes. It is not just a skill—it’s a stance. And it might be our most powerful defense against a digital culture that too often rewards speed over thought and spectacle over understanding.

If we want teens to take misinformation seriously, we must first take seriously the emotional landscapes they navigate, the peer dynamics that shape their choices, and the ethical instincts they are still developing. Misinformation exploits what young people do not know, but it also preys on what they do not yet pause to consider. By creating space in our classrooms for empathy, reflection, and ethical dialogue, we do more than correct falsehoods—we equip the next generation to shape a more thoughtful, responsible digital world. The stakes involve not just facts and fakes but who we become when we share them.

References

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). 2015. “2015 CASEL Guide: Effective Social and Emotional Learning Programs—Middle and High School Edition.” Chicago, IL: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5532b947e4b0edee99477d27/t/5d0948b6a78e0100015f652f/1560889545559/CASEL+Secondary+Guide+2015.pdf

Corbu, N., Oprea, D.-A., and Frunzaru, V. 2022. “Romanian Adolescents, Fake News, and the Third-Person Effect: A Cross-Sectional Study.” Journal of Children and Media 16 (3): 387–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2021.1992460

Dallacqua, A. K., Sheahan, A., and Davis, A. N. 2022. “Teaching the Comic Yummy to Engage Adolescent Empathy, Critical Reflection, and Community Awareness.” Journal of Moral Education 51 (3): 404–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2021.1890554

Dewi, Y. T., Pratisti, W. D., and Prasetyaningrum, J. 2020. “The Effect of Roleplay to Increase Empathy Toward Students with Disruptive Classroom Behavior.” 2019: Proceeding ISETH, pp. 210–19. https://proceedings.ums.ac.id/iseth/article/view/1334

Eva, Nicole, and Erin Shea. 2018. “Marketing libraries in an era of “fake news”.” Reference & User Services Quarterly 57, no. 3, 168-171. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90019879

Figueira, Á., and Oliveira, L. 2017. “The Current State of Fake News: Challenges and Opportunities.” Procedia Computer Science, 121, 817–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.106

Herrero-Diz, P., Conde-Jiménez, J., and Reyes de Cózar, S. 2020. “Teens’ Motivations to Spread Fake News on WhatsApp.” Social Media + Society 6 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120942879

Howard, P. N., Neudert, L.-M., Prakash, N., and Vosloo, S. 2021. “Digital Misinformation / Disinformation and Children.” United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Retrieved on February 20 (2021). https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/reports/digital-misinformation-disinformation-and-children

Loos, E., Ivan, L., and Leu, D. 2018. “‘Save the Pacific Northwest Tree Octopus’: A Hoax Revisited. Or: How Vulnerable Are School Children to Fake News?” Information and Learning Science 119, no. 9/10, 514–528. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-04-2018-0031

Mahmoud, A. 2024. “The Short-Term Effect of Interactive Drama and Reflective Writing on Adolescents’ Social-Emotional Learning Core Competencies: A Five-Week Intervention.” Preprint, Research Square, June 19, 2024. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4461803/v1

Marathe, A., and Sen, A. 2021. “Empathetic Reflection: Reflecting with Emotion.” Reflective Practice 22 (4): 566–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2021.1927693

Marwick, A. E., and Boyd, D. 2014. “Networked Privacy: How Teenagers Negotiate Context in Social Media.” New Media & Society 16 (7): 1051–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814543995

McCarthy, C. 2018. “Why Teenagers Eat Tide Pods.” Harvard Health Publishing (blog), January 30, 2018, https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/why-teenagers-eat-tide-pods-2018013013241

Mihailidis, P., and Viotty, S. 2017. “Spreadable Spectacle in Digital Culture: Civic Expression, Fake News, and the Role of Media Literacies in ‘Post-Fact’ Society.” American Behavioral Scientist 61 (4): 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217701217

Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). 2023. “Social Media and Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory”. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; PMID: 37721985. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37721985/

Wilson, Carolyn, Alton Grizzle, Ramon Tuazon, Kwame Akyempong, and Chi-Kim Cheung. 2011. “Media and Information Literacy Curriculum for Teachers.” United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/media-and-information-literacy-curriculum-teachers